Release Date: September 13, 1994

Sweet Sorrow

Chill

Rejoice

Faith

Alone In The Morning

Mischief

Dialogue

The Oneness Of Two (In Three)

Past In The Present

Obsession

Headin' Home

Players:

Joshua Redman (saxophone),Brad Mehldau (piano), Christian McBride (bass), Brian Blade (drums)

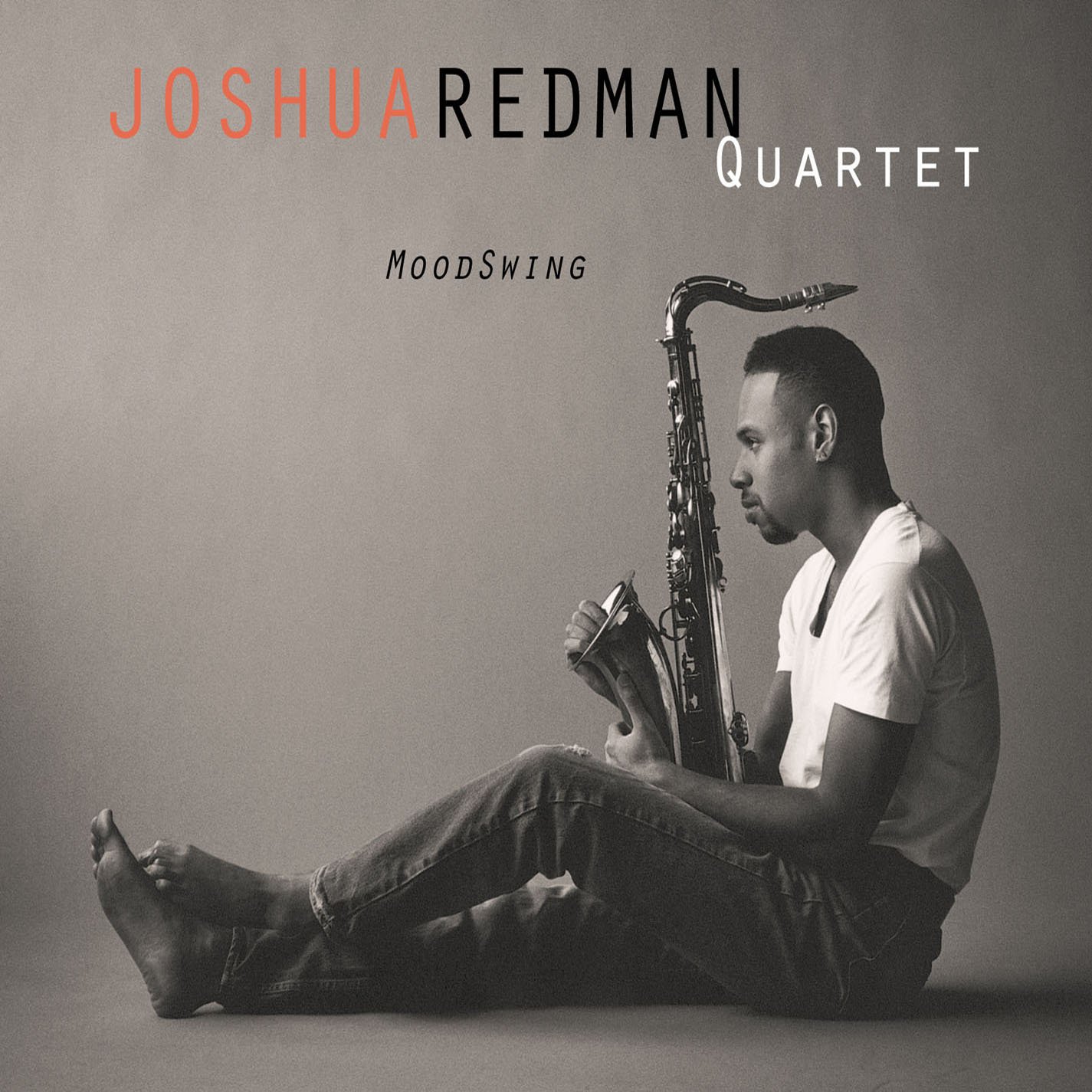

MoodSwing

On his third album, Joshua Redman joined forces with some of the most exciting younger players in jazz—each a virtuoso on his instrument, and each now a celebrated leader in his own right: pianist Brad Mehldau, bassist Christian McBride, and drummer Brian Blade. But don't expect youthful indiscretion here: as its name suggests, Moodswing is built on sophisticated grooves, along with a fresh, in-the-pocket band sound that would be a wonder at any age. And just what "moods" is this stellar quartet "swinging"? The song titles tell the story: the plaintive sound of "Sweet Sorrow"; the sly, easy swing of "Chill"; the stately grace of "Faith;" the playful bounce of "Mischief." But no matter the sound being explored, with these players, it's always the feeling that counts.

As Joshua himself put it, "Jazz is music. And great jazz, like all great music, attains its value not through intellectual complexity but through emotional expressivity. True, jazz is a particularly intricate, refined, and rigorous art form…. Yes, jazz is intelligent music. Nevertheless, extensive as they might seem, the intellectual aspects of jazz are ultimately only means to its emotional ends. Technique, theory, and analysis are not, and should never be considered ends in themselves."

In 2009, Nonesuch reissued MoodSwing on 180-gram vinyl.

LINER NOTES

Jazz is suffering today, but not in the way you might think. Contrary to the warnings of some professional (and amateur) pessimists, jazz in the 90’s is alive and well. It is thriving, creative, inspired, provocative, and original. What jazz suffers from today is not artistic stagnation but popular mystification. Jazz, in other words, has a rotten public image – an image which was epitomized in a comment an acquaintance made to me just the other day:

“Jazz is cool and all, but it’s not really my type of thing. I mean, I respect it, but I can’t really get into it. I like music that makes me feel something. Jazz isn’t really about that. With jazz, you gotta think all the time. Jazz is all complicated and weird. It’s for those special types of people who like talking about stuff and figuring things out. Jazz is way too deep for me.”

This exact same view has been voiced innumerable times in countless different ways by jazz skeptics the world over. All jazz musicians are aware of it. Some ignore it. Some deny it. Some take great offense at it. Some have heard it expressed so often that they even begin to believe it themselves. But regardless of what specific forms this idea takes or what varying reactions it engenders, its central premise remains constant and abundantly clear: Jazz is an intellectual music.

According to popular notion, jazz is something which you research and study, inspect and dissect, scrutinize and analyze. Jazz twists your brain like an algebraic equation, but leaves your body lifeless and limp. In the eyes of the general public, jazz appears as an elite art form, reserved for a select group of sophisticated (and rather eccentric) intelligentsia who rendezvous in secret, underground haunts (or inaccessible ivory towers) to play obsolete records, debate absurd theories, smoke pipes, and read liner notes. Most people assume that the appreciation of jazz is a long, arduous, and painfully serious cerebral undertaking. Jazz might be good for you, but it just isn’t any fun.

This image is simple, powerful, and dangerously appealing.

But it is also egregiously false.

Jazz is music. And great jazz, like all great music, attains its value not through intellectual complexity but through emotional expressivity. True, jazz is a particularly intricate, refined, and rigorous art form. Jazz musicians must amass a vast body of idiomatic knowledge and cultivate an acute artistic imagination if they wish to become accomplished, creative improvisers. Moreover, a familiarity with jazz history and theory will undoubtedly enhance a listener’s appreciation of the actual aesthetics. Yes, jazz is intelligent music. Nevertheless, extensive as they might seem, the intellectual aspects of jazz are ultimately only means to its emotional ends. Technique, theory, and analysis are not, and should never be considered, ends in themselves.

Jazz is not about flat fives or sharp nines, or metric subdivisions, or substitute chord changes. Jazz is about feeling, communication, honesty, and soul. Jazz is not supposed to boggle the mind. Jazz is meant to enrich the spirit. Jazz can create jubilance. Jazz can induce melancholy. Jazz can energize. Jazz can soothe. Jazz can make you shake your head, clap your hands, and stomp your feet. Jazz can render you spellbound and hypnotized. Jazz can be soft or hard, heavy or light, cool or hot, bright or dark. Jazz is for your heart.

Jazz moves you.

If, then, the popular perception of jazz as an intellectual exercise is at odds with the reality of jazz as an emotional experience, what is to be done? How is jazz to be demystified? How can its image be revamped? These are problems which must be solved primarily by image-makers. Dedicated jazz musicians must concentrate first and foremost on their music. Still, when appropriate opportunities do arise, jazz musicians could greatly further the cause by de-mystifying peripheral theoretical jazz issues and instead directing attention toward the expressive core of their art.

That’s why, in writing about this recording, I’m going to refrain from technical discussions. I don’t want to talk about notes, phrases, chords, or meters. I won’t wax eloquently about melodic inversions, harmonic modulations, or polyrhythmic permutations. And I refuse to get bogged down in painfully-detailed, play-by-play, analyses of the various performances. (Besides, I have to leave something for other people to write about.) I actually have very little to say about this music, which I hope will speak clearly enough for itself.

I want just one thing to be known: Every composition on this recording exists to evoke a mood. Whether it be the hearty exuberance of “Rejoice,” the roguish playfulness of “Mischief,” the wistful reminiscence of “Past In The Present,” or the relaxed hipness of “Chill” – each song seeks to express a feeling, to conjure a spirit, to tell a moving, emotional story.

All these moods are, of course, general and open-ended. There is no single, ideal way to express the “Sweet Sorrow” of two lovers parting, or the “Oneness” of their reunion. There are no constant, definitive musical sounds which communicate the joyful anticipation you feel as you’re “Headin’ Home” after months on the road, or the crisp melancholy you experience waking up “Alone In The Morning,” or the “Faith” we all need to persevere through the dark periods of life. Similarly, none of these compositions possesses anything resembling a precise, literal meaning. No need to trouble youself wondering about the exact nature of my “Obsession,” or the specific subject of our “Dialogue.” Each composition intimates an endless number of potential meanings and permits an infinite variety of expressive interpretations.

Jazz is, after all, an improvised music. It demands sensitivity, spontaneity, and flexibility on the part of performers and listeners alike. The magic of the jazz experience lies in its irreplicability. Every sound is precious because it will never be played (or heard) in precisely the same way, at the same moment, in the same place, with the same feeling.

Thus it is best to think of these compositions not as exhaustive aesthetic dissertations but as loose tonal suggestions. Each song implies a basic mood. Each tune establishes an overall theme. After that it is up to us, as improvising musicians, to take these themes and weave them into personalized, inspired, spontaneous narratives. And it is up to you, as listeners, to take these moods and use them as windows to your own souls. Ultimately, these songs will be about your experiences, your impressions, and your emotions. They can mean whatever you want them to mean. They can be whatever you imagine them to be. They can take you wherever you wish to go.

So long as they make you feel.

—Joshua Redman April, 1994